In a previous post (When eagles go bad) I mentioned Haast’s eagle, a giant extinct species from New Zealand that would have been capable of some awesome predatory behaviour. Here, we look at this species in more detail.

Until recently New Zealand truly was a land of birds. Inhabited by the 11 (or so) species of moa (future blog post to come on that), the long-beaked kiwis, snipes and snipe-rails, the bizarre adzebills, a variety of rails and coots, flightless ducks and geese, giant terrestrial owlet-nightjars, diminutive New Zealand wrens, and a motley assortment of crows, quails, mergansers, parrots, wattlebirds, thrush-like passerines, owls, honeyeaters and herons, it would appear to be the ideal place for birds of prey to evolve, and to take predatory advantage of this diverse avifauna. We now know that New Zealand was inhabited until very recent times by at least two such birds of prey, and both/all were specialised bird predators [an alleged third species, a sea eagle described from Chatham Island in 1973 and dubbed Haliaeetus australis, has proved to be a mis-labelled North American Bald eagle H. leucocephalus. A fourth species, the New Zealand falcon Falco novaeseelandiae, has survived to the present].

The first of the two bird predators was originally described as a very large harrier, and called Circus eylesi by Ron Scarlett in 1953. With large females perhaps weighing as much as 3 kg, this was a giant if it were a harrier: living species rarely weigh more than 700 g (Clarke 1990). Scarlett later regarded the bird as a giant goshawk however (a member of the genus Accipiter), a specialist bird-catcher adept at flying through tangled woodland habitats. Though the goshawk reidentification has become quite well known, new examination has demonstrated that the attribution of the species to Circus was correct. It really was a gigantic, bird-killing member of the group (and whether it is one or two species still remains contested).

The second New Zealand bird of prey was the biggest eagle EVER - the enormous Haast’s eagle Harpagornis moorei Haast 1872, a powerful forest giant that some experts have imagined as being something like the modern Harpy eagle Harpia harpyja. As will be discussed in part II, new data indicates that the generic name Harpagornis is invalid, but we won’t worry about that now [part II now available here].

Introducing Haast’s eagle

Haast’s eagle has been known to science since 1871, but until recently virtually nothing was known of how it may have lived, or how it was related to other kinds of eagles. Several publications on Haast’s eagle addressing these problems were produced by Richard Holdaway in the late 1980s and 1990s following his 3-volume doctoral dissertation and a huge amount of information on the bird was recently compiled by Trevor Worthy and Holdaway for their superb book The Lost World of the Moa. Go there if you are even vaguely interested; you won’t regret it.

The first Haast’s eagle material to be discovered by Europeans was found by Frederick Fuller at the moa excavation site at Glenmark swamp, Canterbury, in 1871. Johann Franz Julius Haast (1822-1887), director of the Canterbury Museum and noted expert on moa and other New Zealand birds, read a description of the species to the Philosophical Society of Canterbury in 1871, and published his description the following year (Worthy & Holdaway 2002). He named the bird after George Moore, the owner of Glenmark Station. This association of Haast’s eagle with moa immediately led to suggestions that it was a moa-hunter, and had perhaps come to feed on moa that had become trapped in the mud of the swamps.

Subsequent finds showed the eagle to be widely distributed on South Island and the southern half of North Island. However, even before its official extinction date, it seems to have been rare or absent from the eastern coast of central North Island (Horn 1983) and quite why it was never widely distributed in the northern half of North Island, which at this time was heavily forested and apparently ideal for the bird, remains a mystery. Like other giant birds of prey around the world, Haast’s eagle does not appear to have been common at any locality and its remains are not particularly abundant: only three complete skeletons are known, the most recently discovered being reported in 1990. This specimen was discovered at the bottom of a narrow vertical sinkhole and seems to have fallen accidentally to its death (Worthy & Holdaway 2002).

As in most birds of prey, female Haast’s eagles were larger than males. In estimated weight they were 10-13 kg and, though (in keeping with its probable forest-dwelling lifestyle) their wings were proportionally short, they still had a wingspan of around 2.6 m. The standing height of a female Haast’s eagle has been estimated as 1.1 m. Male Haast’s eagles, which were initially regarded as a separate species (H. assimilis Haast 1874), probably weighed 9-10 kg. For comparison, the largest living eagles, the Harpy Harpia harpyja, Philippine eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi and European Haliaeetus albicilla and Steller’s sea eagles H. pelagicus, rarely exceed 2.4 m in wingspan. Some female H. albicilla have been recorded with wingspans of 2.65 m and a large female H. pelagicus may reach 9 kg (Brown 1976, Burton 1989). Amongst living birds of prey, only condors exceed these measurements - the Andean condor Vultur gryphus possibly exceeding 3 m in wingspan and reaching 12 kg.

The skull of Haast’s eagle measures 15 cm in total length and is elongate, looking something like a stretched version of an Aquila skull, and without the tremendously deep beak seen in some forest eagles like Pithecophaga and Harpia. The skull is actually superficially rather like that of an Old World vulture and, unlike other aquiline eagles, the nostril in Haast’s eagle was partially closed-off by ossification around its rostral, dorsal and ventral margins. This recalls the presence of an accessory bony plate that covers part of the nostril opening in some of the larger Old World vultures. The legs and feet of Haast’s eagle were tremendously robust and powerful and appear well capable of dispatching very large prey. Its claws are massive, strongly curved and, with their external keratin sheath, would have reached 75 mm in length. A complete, thorough description of the osteology of Haast’s eagle was provided by Worthy & Holdaway (2002): the premiere source of information on this bird.

While some material dates Haast’s eagle to around 30,000 years before present, its youngest remains show that it was still around about 500 years ago, and it therefore most probably became extinct at around the same time as (or slightly before) the moa. Presumably, as moa hunting became more intense and moa became rarer and rarer, and as habitat degradation on New Zealand increased, Haast’s eagle became increasingly pressurised and eventually unable to sustain a population. A c. 300 year overlap of Haast’s eagle and humans therefore seems to have occurred (the Maori colonised New Zealand at around 850 years before present). Seeing as the Maori have legends of giant predatory birds - including of the sky-dwelling hokioi or hakuwai and the man-eating pou-kai - it has been tempting for writers to speculate that these legends do indeed refer to Haast’s eagle (Reed 1963, Hall 1994). Unfortunately the legends are far too vague for this to be confirmed, but it has led to some very interesting speculations (to be covered in part II).

Surprisingly, much as some people have continued to entertain notions of moa survival to the present day, there have been a number of suggestions that Haast’s eagle did not die out 500 years ago, but survived to within living memory. This idea is based on two lines of evidence: eyewitness accounts of large birds of prey, and reports of unusual unidentified bird calls of a particularly loud and startling nature. The calls were reported from Stewart Island as recently as 1961 and, because the animal making these nocturnal sounds was never seen, it was suggested by some that Haast’s eagle might have been the vocaliser. Needless to say, more likely candidates are on offer and Miskelly (1987) suggested that New Zealand snipe (Coenocorypha) might actually be the culprit.

Alleged eyewitness accounts from recent times are few, and restricted to the 1860s. Haast actually saw what he thought was a giant eagle in the Canterbury mountains, and a large bird that walked into his tent one night was also suggested to be a giant eagle. Even more incredible is Charlie Douglas’ reported shooting of two giant eagles in the Landsborough Valley, both of which, reportedly, had wingspans of 3 m or so. Worthy & Holdaway (2002, p. 335) noted that Douglas was ‘a meticulous observer, he did not seek publicity, and he certainly never claimed that he had seen the “extinct” eagle’. It’s an incredible report, and one that can’t be verified.

To come in a Part II: what kind of eagle was Haast’s eagle?; what did it look like?; and what, and how, did it hunt?

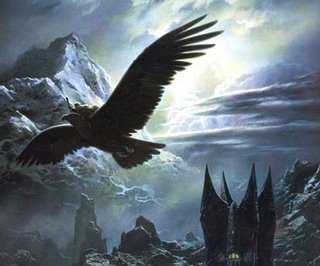

The above picture - which doesn't really depict a Haast's eagle of course - is from kennislink.nl.

Refs - -

Brown, L. 1976. Eagles of the World. David & Charles (Newton Abbot/London/Vancouver).

Burton, P. 1989. Birds of Prey. Gallery Books (London).

Clarke, R. 1990. Harriers of the British Isles. Shire Natural History (Princes Risborough, UK).

Hall, M. A. 1994. Thunderbirds - the living legend! (2nd edition). Privately published (Minneapolis).

Horn, P. L. 1983. Subfossil avian deposits from Poukawa, Hawkes Bay, and the firat record of Oxyura australis (Blue-billed duck) from New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 13, 67-78.

Miskelly, C. M. 1987. The identity of the hakawai. Notornis 34, 95-116.

Reed, A. W. 1963. Treasury of Maori Folklore. A. H. & A. W. Reed (Wellington, NZ).

Worthy, T. H. & Holdaway, T. H. 2002. The Lost World of the Moa. Indiana University Press (Bloomington, Indiana).

Would a bird weighing up to 13 kilograms be agile enough in flight for a predatory lifestyle? Well, obviously it was. But... how? How is that possible? And however did it manage to take off and land?

ReplyDeleteI'm puzzled by the aerodynamics of extinct creatures. Teratorns are bad enough, but at least they weren't active hunters. And the really gigantic pterosaurs mostly seem to have an albatross-type lifestyle, which makes things easier because it's mainly gliding rather than powered flight. But a bird that requires agility for a living?

Hi Lucy. All the answers to your questions can be found in Worthy & Holdaway's book, and if you're seriously interested do check out what they say. They show that Haast's eagle had high wing and span loadings, and that it thus had a high stalling speed and probable low manouevrability.

ReplyDeleteBut note that it didn't need to be agile for, so far as we know, it was not an agile chaser of flying prey, but mostly a predator of terrestrial (often flightless) species.

Takeoff would have been difficult but Worthy & Holdaway show that the estimated amount of pectoral musculature would easily have produced enough power to enable the rapid flapping required to get airborne.

There is loads more info on this subject in Worthy & Holdway.

Thanks for the advice. Worthy and Holdway is very useful.

ReplyDeleteJust one thing that confuses me: Worthy and Holdway give maximum wingspan as 2.6 metres. Are you using a different estimate of primary length, to come up with 3 m?

Now Dr Paul Scofield (Canterbury Museum) and Professor Ken Aswell (NSW University) have published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology on the deduced behaviours of tha Haast's

ReplyDeletehi there,

ReplyDeletei am doing a research project and was just wondering if the extinction of the haasts eagle has effected the food chain at all? if so how?

thanks

hi there

ReplyDeletei was wondering if the eagles its extinction has affected the foodchain if so how?

thanks