Tetrapod Zoology ver 2

It is done: Tetrapod Zoology is moving. Please go over to....

http://scienceblogs.com/tetrapodzoology/

See you on the other side!

"It is the best zoological blog out there, period"

Tetrapod Zoology: horribly biased

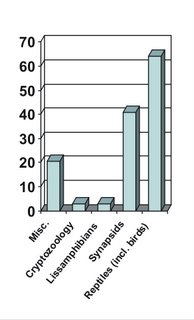

As mentioned in the previous post, given that I do not blog ‘to a plan’, I want to know what the spread of subjects I’ve blogged about might tell me. Might they reflect my ‘real’ interests, or might they perhaps indicate which areas within tetrapod zoology are currently the most happening, interesting or sexy? I don’t know, but I find the results pretty surprising. In terms of broad coverage of subject areas, we see from the adjacent graph [click for larger version, of course] that I’ve written more about reptiles (including birds) than I have about other tetrapod groups. It’s also notable that the number of miscellaneous posts – those that cover various assorted crap and aren’t really focused on any one group of animals – is reasonably high.

As mentioned in the previous post, given that I do not blog ‘to a plan’, I want to know what the spread of subjects I’ve blogged about might tell me. Might they reflect my ‘real’ interests, or might they perhaps indicate which areas within tetrapod zoology are currently the most happening, interesting or sexy? I don’t know, but I find the results pretty surprising. In terms of broad coverage of subject areas, we see from the adjacent graph [click for larger version, of course] that I’ve written more about reptiles (including birds) than I have about other tetrapod groups. It’s also notable that the number of miscellaneous posts – those that cover various assorted crap and aren’t really focused on any one group of animals – is reasonably high.

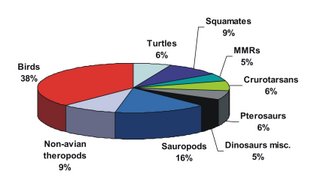

The prevalence of reptiles is not so surprising, given that I specialize on dinosaurs and other Mesozoic reptiles, but what does surprise me is how the reptiles break down when we look at them by group. Turtles, crurotarsans (the clade that includes crocodilians and their extinct relatives) and pterosaurs are equally represented, but with only a few posts each. Despite (or, perhaps, because of) the fact that I have just been working on them for seven years, non-avian theropods haven’t featured heavily. I must rectify this. Squamates (lizards, snakes and kin) do a bit better, and would have featured even more on the blog if I’d gotten round to finishing the articles I’ve started on sea snakes, island-endemic lizards and anguids. The two most surprising groups are sauropods (represented by 10 posts), and birds (represented by 24 posts). Yikes, does this mean that I’m more ‘interested’ in sauropods and birds – and even squamates – than in non-avian theropods? It’s something for me to think about. The prevalence of birds is just downright scary: more on it in a moment.

The prevalence of reptiles is not so surprising, given that I specialize on dinosaurs and other Mesozoic reptiles, but what does surprise me is how the reptiles break down when we look at them by group. Turtles, crurotarsans (the clade that includes crocodilians and their extinct relatives) and pterosaurs are equally represented, but with only a few posts each. Despite (or, perhaps, because of) the fact that I have just been working on them for seven years, non-avian theropods haven’t featured heavily. I must rectify this. Squamates (lizards, snakes and kin) do a bit better, and would have featured even more on the blog if I’d gotten round to finishing the articles I’ve started on sea snakes, island-endemic lizards and anguids. The two most surprising groups are sauropods (represented by 10 posts), and birds (represented by 24 posts). Yikes, does this mean that I’m more ‘interested’ in sauropods and birds – and even squamates – than in non-avian theropods? It’s something for me to think about. The prevalence of birds is just downright scary: more on it in a moment.

A similarly surprising thing happens when we break down all the mammal posts. Of the groups covered (and keep in mind that a vast number of areas haven’t been covered at all), hoofed mammals are out in front, and rodents and primates are reasonably well represented. This surprises me because I’d always imagined that these were the least interesting mammals: way outclassed by marsupials, monotremes, pangolins, bats and xenarthrans. Yet I’ve hardly blogged at all on any of these topics. Yikes, do I really find deer and voles more interesting than sloths, thylacines and echidnas? Again, it’s something I’ll have to think about, and perhaps aim to rectify in future.

A similarly surprising thing happens when we break down all the mammal posts. Of the groups covered (and keep in mind that a vast number of areas haven’t been covered at all), hoofed mammals are out in front, and rodents and primates are reasonably well represented. This surprises me because I’d always imagined that these were the least interesting mammals: way outclassed by marsupials, monotremes, pangolins, bats and xenarthrans. Yet I’ve hardly blogged at all on any of these topics. Yikes, do I really find deer and voles more interesting than sloths, thylacines and echidnas? Again, it’s something I’ll have to think about, and perhaps aim to rectify in future.

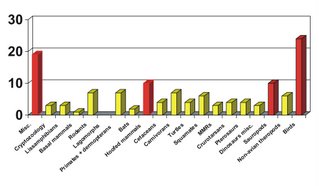

Looking at subject areas broken down more specifically (this time across all material covered), the overall picture is, again, somewhat surprising. Lissamphibians feature poorly and Palaeozoic and Mesozoic amphibian groups like lepospondyls and temnospondyls don’t feature at all. This is bad as I actually spent a lot of time doing research on these groups in 2006. Rodents, primates and turtles are reasonably represented overall (which, again, surprises me as I just never imagined that I’d end up writing much about these groups). The red bars show those subject areas that were particularly well represented: miscellaneous stuff, hoofed mammals, sauropods and birds! There is no way this is what I would have predicted. The big score that birds get is worrying. Granted, I haven’t broken Aves down into constituent clades, so the results aren’t exactly balanced, but – again – I’m asking myself: does this really reflect my personal interests? Am I really more interested in birds than in other tetrapods? Or is it just that birds were particularly newsworthy in 2006? I think that the latter point is significant here, as the posts on eagle owls, phorusrhacids, the

Looking at subject areas broken down more specifically (this time across all material covered), the overall picture is, again, somewhat surprising. Lissamphibians feature poorly and Palaeozoic and Mesozoic amphibian groups like lepospondyls and temnospondyls don’t feature at all. This is bad as I actually spent a lot of time doing research on these groups in 2006. Rodents, primates and turtles are reasonably represented overall (which, again, surprises me as I just never imagined that I’d end up writing much about these groups). The red bars show those subject areas that were particularly well represented: miscellaneous stuff, hoofed mammals, sauropods and birds! There is no way this is what I would have predicted. The big score that birds get is worrying. Granted, I haven’t broken Aves down into constituent clades, so the results aren’t exactly balanced, but – again – I’m asking myself: does this really reflect my personal interests? Am I really more interested in birds than in other tetrapods? Or is it just that birds were particularly newsworthy in 2006? I think that the latter point is significant here, as the posts on eagle owls, phorusrhacids, the

For those who say nice things about my blog, the good news is that this is still just the beginning, and there is a vast amount of material I have yet to complete and post, or even write. Ironically, I still haven’t managed to complete many articles that I have started writing way back at the start of 2006, including those on temnospondyls, rhinogradentians, Haast’s eagle, Piltdown and amphisbaenians. To those looking forward to the posts on these subjects, all I can say it: please bear with me, they will be completed and posted eventually! As I’ve said before, if I could devote more time to blog writing I would. At the moment life gets in the way.

So, happy first birthday Tetrapod Zoology. I hope you’ve enjoyed the ride so far. Many thanks to all those who have helped and supported me over the past year, to those who assist in obtaining literature, to those who advise and point out errors, to those who post comments, and to all who read and/or visit the blog [UPDATE: to see what happened next go here].

On

On So, today is Tetrapod Zoology’s first birthday. In this post (and part II) I want to look back at a year’s blogging: given that I do not really blog ‘to a plan’ (I simply write about those subjects that I bump into, or find particularly interesting on the spur of the moment), I’m interested in seeing what I might learn about my blogging habits. It’s also worth reviewing Tetrapod Zoology’s changing fortunes, and on looking back at my own circumstances, during the year that’s past. You’ll be pleased to hear that we (as in, Toni, Will and myself) celebrated Tetrapod Zoology’s first birthday by visiting the Natural History Museum in

A year in the life

It feels like a lot happened in 2006, though I’m not sure if it really did. I spent time in the field looking at obscure British reptiles and amphibians, wild deer, rodents, bats and birds, and I taught Will stuff about tracking and field sign. I visited the farm many times (see adjacent image), and the zoo where I was impressed by takins, peccaries, sleeping anteaters and rhinos. Feedback on the blog increased and, thanks to it, I made lots of new friends. The main event of 2006 was, of course, the completion of my PhD on Wealden theropods. By repeatedly staying up until 05-00 each morning, I managed to get the thing completed, and at the start of June I had the viva and completed the process in full. Besides being kept busy with my editorial work for Cretaceous Research, in late 2006 I began an adult-education course on the evolution and diversity of tetrapods for the WEA (Workers Educational Authority), and at the start of 2007 I am currently teaching the second such course.

It feels like a lot happened in 2006, though I’m not sure if it really did. I spent time in the field looking at obscure British reptiles and amphibians, wild deer, rodents, bats and birds, and I taught Will stuff about tracking and field sign. I visited the farm many times (see adjacent image), and the zoo where I was impressed by takins, peccaries, sleeping anteaters and rhinos. Feedback on the blog increased and, thanks to it, I made lots of new friends. The main event of 2006 was, of course, the completion of my PhD on Wealden theropods. By repeatedly staying up until 05-00 each morning, I managed to get the thing completed, and at the start of June I had the viva and completed the process in full. Besides being kept busy with my editorial work for Cretaceous Research, in late 2006 I began an adult-education course on the evolution and diversity of tetrapods for the WEA (Workers Educational Authority), and at the start of 2007 I am currently teaching the second such course.

Since completing the PhD I’ve been unable to get a job in academia, despite strenuous efforts, and life has been very hard. However, working on the assumption that I will somehow get back into the system, I have continued to do research when time allows. Several academic projects that have been mentioned on the blog have yet to come to fruition, including that long-delayed manuscript on British dinosaur diversity, and work on Cretaceous Spanish vertebrates, Wealden sauropods, and azhdarchid ecology. In July, Dave Martill and I finally published our paper on Tupuxuara and the affinities of azhdarchoid pterosaurs (to a flurry of media attention), and Dave, Sarah Fielding and I published a review of Kimmeridge Clay dinosaurs later in the year. I am routinely asked to do talks for local natural history and geology groups, and in 2006 I lectured on ichthyosaurs, British big cats and Wealden dinosaurs. I also did TV interviews on theropods and marine reptiles, a podcast for George Kenney’s Electric Politics site, and late in the year I was commissioned to assist in the development of a TV programme featuring computer-generated dinosaurs.

While all of this was going on, I have researched and published blog articles on… well, a lot of stuff (see part II). For me, blogging is great for two main reasons. Firstly, it’s very easy compared to conventional publishing. An article of a 1000 words can be written, illustrated, formatted and published within an hour or so. Secondly, the accessibility and popularity of blogs means that blog posts are almost certainly read by more people than are anything within conventionally published media.

Troughs, peaks and mega-peaks

Naturally, if you maintain a web site of any sort, you’re interested in how much, or how little, traffic you’re getting. Blogspot doesn’t provide a web counter for every blog of course, so the only way to check your traffic is to see how many people have viewed your profile. However, of every 2000 people that visit a blog, perhaps 1 looks at the profile, so this isn’t a reliable guide. So in September I installed a web counter (provided, free by bravenet), and by November 2006 it had counted 50,000 hits, which ain’t bad. At the time of writing, the current number of average daily hits is round about 500 (see adjacent graph, depicting traffic on

Naturally, if you maintain a web site of any sort, you’re interested in how much, or how little, traffic you’re getting. Blogspot doesn’t provide a web counter for every blog of course, so the only way to check your traffic is to see how many people have viewed your profile. However, of every 2000 people that visit a blog, perhaps 1 looks at the profile, so this isn’t a reliable guide. So in September I installed a web counter (provided, free by bravenet), and by November 2006 it had counted 50,000 hits, which ain’t bad. At the time of writing, the current number of average daily hits is round about 500 (see adjacent graph, depicting traffic on

Within a short length of time I learnt that certain types of posts got more hits than others, and this partly explains why – in November 2006 – I blogged about sasquatch. Thanks to the web counter, I was able to watch my traffic soar to a high of about 3000 a day. It seems that mentions of the blog on scienceblogs.com sites and anomalist.com result in a surge of traffic: the graph shown here shows what happened on

Within a short length of time I learnt that certain types of posts got more hits than others, and this partly explains why – in November 2006 – I blogged about sasquatch. Thanks to the web counter, I was able to watch my traffic soar to a high of about 3000 a day. It seems that mentions of the blog on scienceblogs.com sites and anomalist.com result in a surge of traffic: the graph shown here shows what happened on

Continued in part II….

Here’s a little known fact. Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882), the most important biologist of all time, did not spend his entire life as an old man. I despise stereotypes, especially those that are totally erroneous, and whenever I see a picture of ‘old man

Quite the opposite: in fact most of the stuff that

Quite the opposite: in fact most of the stuff that

* Many, many thanks to the good friends who reminded me how old I really am. I was young once.

We know that

We know that

In fact

So, it’s no big deal, but I sooo wish that Darwin, and all those other great scientists, weren’t stereotyped so much. Images of the young, pre-bearded

Moving on: I have been kept busy the last few days with Mesozoic frogs, pterosaurs (again), gazumping and aetosaurs… and I must stop knuckle-walking. It hurts. I’m serious: future post to come on quadrupedality in humans.

For the latest news on Tetrapod Zoology do go here.

Refs - -

Darwin, C. 1859. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. John Murray, London.

Desmond, A. & James, M. 1991. Darwin.

In the previous post we looked at the obscure and poorly known mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus, described in 1878 on the basis of an incomplete but enormous dorsal vertebra and the distal end of a femur. Its details show that it was a diplodocoid, and thus related to more familiar taxa like Diplodocus and Apatosaurus. Despite its absurd size – suggesting (by comparison with other diplodocoids) a total length of 60 m – this material somehow vanished prior to 1921. Due in part to these facts (and also, perhaps, to its poorly publicised and unfamiliar-sounding – or ‘crappy’ – name), Amphicoelias fragillimus was to be all but forgotten in the decades that followed…

In the previous post we looked at the obscure and poorly known mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus, described in 1878 on the basis of an incomplete but enormous dorsal vertebra and the distal end of a femur. Its details show that it was a diplodocoid, and thus related to more familiar taxa like Diplodocus and Apatosaurus. Despite its absurd size – suggesting (by comparison with other diplodocoids) a total length of 60 m – this material somehow vanished prior to 1921. Due in part to these facts (and also, perhaps, to its poorly publicised and unfamiliar-sounding – or ‘crappy’ – name), Amphicoelias fragillimus was to be all but forgotten in the decades that followed…During the 1990s, little-known articles by John McIntosh (revered older statesman of sauropod research) and Greg Paul looked briefly at A. fragillimus. McIntosh (1998) went through Cope’s inventories of the

The news is that, at long last, a proper reappraisal of this mysterious giant has finally appeared: it’s a new paper by Ken Carpenter of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, and while, sadly, it doesn’t report the discovery of a new, articulated A. fragillimus specimen, it does cover pretty much everything we know about this dinosaur (Carpenter 2006). By the way, Carpenter and colleagues have tried looking for additional remains of A. fragillimus, thus far without success. Actually, I have to note here the rumour that new A. fragillimus material has been discovered, and that it will be discussed at the 2008 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. We shall see [adjacent image is Cope’s original 1878 figure of the A. fragillimus vertebra. I ripped it off from Matt Celeskey’s post about A. fragillimus from August of last year (go here). Sorry Matt].

The news is that, at long last, a proper reappraisal of this mysterious giant has finally appeared: it’s a new paper by Ken Carpenter of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, and while, sadly, it doesn’t report the discovery of a new, articulated A. fragillimus specimen, it does cover pretty much everything we know about this dinosaur (Carpenter 2006). By the way, Carpenter and colleagues have tried looking for additional remains of A. fragillimus, thus far without success. Actually, I have to note here the rumour that new A. fragillimus material has been discovered, and that it will be discussed at the 2008 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. We shall see [adjacent image is Cope’s original 1878 figure of the A. fragillimus vertebra. I ripped it off from Matt Celeskey’s post about A. fragillimus from August of last year (go here). Sorry Matt].

Was A. fragillimus a hoax?

Unsurprisingly, quite a few people have been sceptical about the existence of this all-too-conveniently lost mega-sauropod. Can we be sure that it ever really existed, or could it be that Cope was pulling a fast one in order to beat his rival, Othniel Charles Marsh, hands-down in an effort to describe the biggest sauropod? As attractive as this scenario might appear, hoaxing is highly, highly unlikely. Consider the following:-

-- Cope was very specific about all the discovery details of A. fragillimus. According to his field notes, it was collected in late 1877 by Oramel Lucas (described by Cope as his ‘indefatigable friend’) at

-- Furthermore, the shipment records discovered by McIntosh show that Oramel Lucas and his brother Ira knew of A. fragillimus and labelled some remains with this name (McIntosh 1998, p. 487 and p. 498). If it was a hoax, then the Lucas brothers must have been in on it too, which now makes it a conspiracy.

-- The conspiracy would have to extend even further, as an

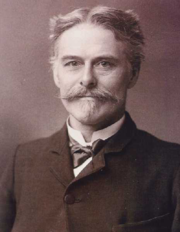

-- The rivalry that existed between Cope and Marsh is also relevant here (Marsh is pictured at left). As is well known, Marsh enjoyed making a very public fool of Cope when he made a technical error (Storrs 1994, Davidson 2002), and when he disagreed with Cope, or thought him wrong, Marsh was tediously pedantic in his criticisms (see Marsh’s 1873 papers on dinoceratans, for example). Marsh never criticised, nor even questioned, the reality of A. fragillimus. Carpenter (2006) notes that ‘Marsh is known to have employed spies to keep tabs on what Cope was collecting, and it is quite possible that he had independent confirmation for the immense size of A. fragillimus’ (p. 134).

-- The rivalry that existed between Cope and Marsh is also relevant here (Marsh is pictured at left). As is well known, Marsh enjoyed making a very public fool of Cope when he made a technical error (Storrs 1994, Davidson 2002), and when he disagreed with Cope, or thought him wrong, Marsh was tediously pedantic in his criticisms (see Marsh’s 1873 papers on dinoceratans, for example). Marsh never criticised, nor even questioned, the reality of A. fragillimus. Carpenter (2006) notes that ‘Marsh is known to have employed spies to keep tabs on what Cope was collecting, and it is quite possible that he had independent confirmation for the immense size of A. fragillimus’ (p. 134).

-- Cope’s drawing of A. fragillimus is accurate-looking and elaborate, and his description refers to small detailed features, all of which conform in details with what we know of diplodocoid vertebrae (part of the description is reproduced at left: from here). He would have to have made all of this stuff up if the specimen was a hoax: it’s not as if the only record of A. fragillimus is a scribbled fragment in a diary, saying ‘On Tuesday I saw the biggest vertebra ever… it was thiiiiis big…’. Rather, the material is documented, in detail, in a proper technical paper. To hoax an entire paper of this sort would be severe science-crime, and there is no indication that Cope was unscrupulous or dastardly, or prepared to stoop this low.

-- Cope’s drawing of A. fragillimus is accurate-looking and elaborate, and his description refers to small detailed features, all of which conform in details with what we know of diplodocoid vertebrae (part of the description is reproduced at left: from here). He would have to have made all of this stuff up if the specimen was a hoax: it’s not as if the only record of A. fragillimus is a scribbled fragment in a diary, saying ‘On Tuesday I saw the biggest vertebra ever… it was thiiiiis big…’. Rather, the material is documented, in detail, in a proper technical paper. To hoax an entire paper of this sort would be severe science-crime, and there is no indication that Cope was unscrupulous or dastardly, or prepared to stoop this low.

-- It is noteworthy that workers well known for their methodical and conservative approach to sauropod studies (notably John McIntosh) have accepted Cope at his word. Osborn, who succeeded Cope as vertebrate palaeontologist for the US Geological Survey and is well known for speaking his mind when he had a problem with something, also never voiced doubts about A. fragillimus.

All of this is circumstantial, for sure, but I agree with Carpenter (and others) that the idea of Cope perpetrating a hoax of this magnitude is pretty much unthinkable. I think we have to assume that the specimens really existed. Therefore, they must have become lost or destroyed some time between 1878 and 1921 (when Osborn and Mook failed to find them). As Carpenter (2006) points out, it in fact appears likely that the material was too fragile to survive, and that it crumbled to bits some time after its discovery. Matt Celeskey also noted this possibility (go here). Cope commented on this fragility, writing ‘in the extreme tenuity of all its parts, this vertebra exceeds this type of those already described, so that much care was requisite to secure its preservation’ (p. 563), and his drawing also suggests that the vertebra had been subjected to extensive weathering and hence was already fragile. Indeed its fragile nature explains the specific name he chose for it.

Furthermore, ‘preservatives had not yet been employed to harden fossil bones, the first of which was a sodium silicate solution used in O. C. Marsh’s preparation lab at

The other Amphicoelias

As I’ve now mentioned a few times, the detailed anatomy of the A. fragillimus vertebra (as figured by Cope) shows us that this sauropod was a diplodocoid. We can make a confident statement like this because it is relatively easy to distinguish the different sauropod clades on the basis of their vertebral anatomy, and A. fragillimus has all the distinctive anatomical features typical of diplodocoids. In fact it strongly resembles the vertebrae of the first named species of Amphicoelias, A.

A.

A.

Was Cope right in referring his second Amphicoelias species to the same genus as the first? Several authors have thought so, and in fact have gone so far as to state that ‘it is doubtful … if the characters described by Cope warrant the placing of the type [of A. fragillimus] in another species different from A. altus’ (Osborn & Mook 1921, p. 279), or ‘there is no reason not to consider [A. fragillimus] a very large individual of A. altus’ (McIntosh 1998, p. 502). If this is true then, like A.

Carpenter argues in his new paper that, in fact, A. fragillimus seems to have differed from A.

One final thing. What’s with the image at the top of the page? I discovered it while googling Amphicoelias. Huh, in my day the only decent zoid was Hellrunner... For the story on the image at left go here (no, that’s not an Amphicoelias vertebra, it’s Matt Wedel. The bone, however, is from a diplodocoid... although not an Amphicoelias), and for previous posts on sauropods see the series on ‘Angloposeidon’, the Christmas post on Turiasaurus, some assorted ramblings on British Wealden sauropods, and a post devoted entirely to the anatomy of their hands.

One final thing. What’s with the image at the top of the page? I discovered it while googling Amphicoelias. Huh, in my day the only decent zoid was Hellrunner... For the story on the image at left go here (no, that’s not an Amphicoelias vertebra, it’s Matt Wedel. The bone, however, is from a diplodocoid... although not an Amphicoelias), and for previous posts on sauropods see the series on ‘Angloposeidon’, the Christmas post on Turiasaurus, some assorted ramblings on British Wealden sauropods, and a post devoted entirely to the anatomy of their hands.Refs - -

Carpenter, K. 2006. Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus Cope, 1878.

Cope, E. D. 1878. On the saurians recently discovered in the Dakota Beds of Colorado. The American Naturalist 12 (2), 71-85.

Davidson, J. P. 2002. Bonehead mistakes: the backround in scientific literature and illustrations for Edward Drinker Cope’s first restoration of Elasmosaurus platyurus. Proceedings of the

McIntosh, J. S. 1998. New information about the Cope collection of sauropods from

Osborn, H. F. & Mook, C. C. 1921. Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias and other sauropods of Cope. Memoirs of the

Paul, G. S. 1994a. Big sauropods – really, really big sauropods. The Dinosaur Report Fall 1994, 12-13.

- . 1994b. Is Garden Park home to the world’s largest known land animal? Tracks in Time 4 (5), 1.

Labels: archosaurs, dinosaurs, Mesozoic, sauropods

Finally, it’s that post on gigantic mega-sauropods you’ve all been oh-so-patiently waiting for. Note that I’ve decided to do a new thing, and have left the ‘teaser post’ on its own (rather than over-writing it with this new version). Talking of new things, recall that something about my blogging habits is set to change soon.. the word is already on the street (to use the words of Carel Brest van Kempen), but I’m going to keep quiet about it for a bit longer. All will be revealed [UPDATE: go here for the news]. Anyway, to business. Even if you’re not an expert on dinosaurs, it’s likely that you’ve heard – firstly – that some sauropods were rily, rily big and – secondly – that these biggest of the big included such whoppers as Seismosaurus, Supersaurus and Argentinosaurus. It’s always helpful that their names are easy to remember. Recent work has not only resulted in the publication of reasonably accurate size estimates for these dinosaurs, it has also clarified their taxonomy and phylogenetic positions.

Finally, it’s that post on gigantic mega-sauropods you’ve all been oh-so-patiently waiting for. Note that I’ve decided to do a new thing, and have left the ‘teaser post’ on its own (rather than over-writing it with this new version). Talking of new things, recall that something about my blogging habits is set to change soon.. the word is already on the street (to use the words of Carel Brest van Kempen), but I’m going to keep quiet about it for a bit longer. All will be revealed [UPDATE: go here for the news]. Anyway, to business. Even if you’re not an expert on dinosaurs, it’s likely that you’ve heard – firstly – that some sauropods were rily, rily big and – secondly – that these biggest of the big included such whoppers as Seismosaurus, Supersaurus and Argentinosaurus. It’s always helpful that their names are easy to remember. Recent work has not only resulted in the publication of reasonably accurate size estimates for these dinosaurs, it has also clarified their taxonomy and phylogenetic positions.  Supersaurus vivianae from the Morrison Formation of Colorado is, despite its name, a valid taxon – specifically it’s a diplodocid diplodocoid, and apparently an apatosaurine (the image at the top of page shows a new skeletal mount of this taxon). Recent estimates put its total length at 33 m. The most oft-figured bit of Supersaurus is its immense scapulocoracoid: it’s usually depicted with the late Jim Jensen, its discoverer and describer, lying alongside it. For a change, here (at left) is a curious new take on the theme (borrowed from here). Oh, and if you’re wondering about Ultrasauros (originally informally named Ultrasaurus: note the spelling difference), it’s no longer regarded as a valid taxon: the type material - a dorsal vertebra - was shown by Brian Curtice and colleagues (Curtice et al. 1996) to belong to Supersaurus (come back Brian, all is forgiven!) while the famous Ultrasauros scapulocoracoid seems to belong to Brachiosaurus. Below, at left, you can see dead fish expert Graeme Elliott standing alongside the Ultrasauros scapulocoracoid (go here for hilarious caption, sorry Graeme).

Supersaurus vivianae from the Morrison Formation of Colorado is, despite its name, a valid taxon – specifically it’s a diplodocid diplodocoid, and apparently an apatosaurine (the image at the top of page shows a new skeletal mount of this taxon). Recent estimates put its total length at 33 m. The most oft-figured bit of Supersaurus is its immense scapulocoracoid: it’s usually depicted with the late Jim Jensen, its discoverer and describer, lying alongside it. For a change, here (at left) is a curious new take on the theme (borrowed from here). Oh, and if you’re wondering about Ultrasauros (originally informally named Ultrasaurus: note the spelling difference), it’s no longer regarded as a valid taxon: the type material - a dorsal vertebra - was shown by Brian Curtice and colleagues (Curtice et al. 1996) to belong to Supersaurus (come back Brian, all is forgiven!) while the famous Ultrasauros scapulocoracoid seems to belong to Brachiosaurus. Below, at left, you can see dead fish expert Graeme Elliott standing alongside the Ultrasauros scapulocoracoid (go here for hilarious caption, sorry Graeme).

Moving on, Seismosaurus hallorum (originally described as S. halli), from the Morrison Formation of New Mexico, is also a diplodocid diplodocoid, but recent work indicates that it is not generically distinct from Diplodocus and should thus be renamed Diplodocus hallorum. Originally claimed to be over 40 m long, new estimates put it between 30 and 35 m. Supersaurus and Diplodocus hallorum, being relatively gracile diplodocids, probably weighed between 25 and 50 tons (Paul 1994a, b, 1997).

Moving on, Seismosaurus hallorum (originally described as S. halli), from the Morrison Formation of New Mexico, is also a diplodocid diplodocoid, but recent work indicates that it is not generically distinct from Diplodocus and should thus be renamed Diplodocus hallorum. Originally claimed to be over 40 m long, new estimates put it between 30 and 35 m. Supersaurus and Diplodocus hallorum, being relatively gracile diplodocids, probably weighed between 25 and 50 tons (Paul 1994a, b, 1997).

A few more super-sauropods have been added to the list in recent years. Most are titanosaurs, the predominantly Cretaceous sauropod clade originally thought to be late-surviving relatives of diplodocoids but now known to be close kin of the short-skulled camarasaurs and brachiosaurs. Argentinosaurus huinculensis, named in 1993, is a huge titanosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Río Limay Formation of Argentina: it was perhaps 30 m long. Paralititan stromeri is another massive titanosaur, this time from the Upper Cretaceous of Egypt. Estimated by its describers as having been around 30 m long, it has more recently been down-sized to a mere 26 m (image below left is Todd Marshall’s painting of Paralititan, taken from here. Go here for yours truly posing in bizarre fashion with the same image). Puertasaurus reuili, named in 2005 and from the Upper Cretaceous Pari Aike Formation of Argentina, was similar in size to these forms. Finally, Turiasaurus riodevensis is a gigantic Spanish form, and it’s not a titanosaur, belonging instead to a hitherto unrecognised clade termed Turiasauria. It was described at the end of 2006 (go here for more) and is one of the biggest sauropods known, with a length of 36-39 m.

Exactly how heavy these mega-sauropods were is mildly controversial. Accurate mass estimates generally agree that they were on the order of 80-90 tons, but Royo-Torres et al. (2006), the describers of Turiasaurus, put this animal at half this. However, they used a notoriously unreliable method of estimating weight.

Exactly how heavy these mega-sauropods were is mildly controversial. Accurate mass estimates generally agree that they were on the order of 80-90 tons, but Royo-Torres et al. (2006), the describers of Turiasaurus, put this animal at half this. However, they used a notoriously unreliable method of estimating weight.

While you might have heard of Supersaurus, Seimosaurus or Argentinosaurus – and perhaps even Turiasaurus and Paralititan – have you heard of… Amphicoelias fragillimus? Well, ok, if you’re a dinosaur ubernerd then the answer will be yes, but not if you’re a normal person. Though described as long ago as 1878, this sauropod has remained decidedly obscure and hardly heard of until pretty recently. I’ve done my part for the cause, having mentioned it at every opportunity: in both Dinosaurs of the

Amphicoelias fragillimus, giant of giants

In August 1878 the famous and prolific scientist* Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897), portrait at left, described a new immense sauropod, Amphicoelias fragillimus, from the

In August 1878 the famous and prolific scientist* Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897), portrait at left, described a new immense sauropod, Amphicoelias fragillimus, from the

* Though usually described (by palaeontologists) as a palaeontologist, Cope was also an accomplished herpetologist and ichthyologist, which explains the name of the journal Copeia.

If history were fair, we would all have grown up familiar with Cope’s hyper-enormous Amphicoelias fragillimus, and we would be less impressed by Brachiosaurus and Balaenoptera, let alone with paltry little 20-m long sauropods like ‘Angloposeidon’ (go here). But it was not to be, and it was to sink into the morass of obscurity. In a major 1921 review of Cope’s sauropods, Henry Fairfield Osborn and Charles Mook noted that they were unable to locate the immense vertebra in Cope’s sauropod collection (Osborn & Mook 1921), today at the

And… I’ll have to stop there. The rest of the story will come in part II: I am aiming to post it tomorrow (

Refs - -

Cope, E. D. 1878. A new species of Amphicoelias. American Naturalist 12, 563-565.

Curtice, B. D., Stadtman, K. L. & Curtice, L. J. 1996. A reassessment of Ultrasauros macintoshi (Jensen, 1985). In Morales, M. (ed) The Continental Jurassic.

Davidson, J. P. 2002. Bonehead mistakes: the backround in scientific literature and illustrations for Edward Drinker Cope's first restoration of Elasmosaurus platyurus. Proceedings of the

McIntosh, J. S. 1998. New information about the Cope collection of sauropods from

Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. 2001. Saurischian dinosaurs 1: Sauropods. In Martill, D. M. & Naish, D. (eds) Dinosaurs of the

Osborn, H. F. & Mook, C. C. 1921. Camarasaurus, Amphicoelias and other sauropods of Cope. Memoirs of the

Paul, G. S. 1994a. Is

- . 1994b. Big sauropods – really, really big sauropods. The Dinosaur Report Fall 1994, 12-13.

- . 1997. Dinosaur models: the good, the bad, and using them to estimate the mass of dinosaurs. In Wolberg, D. L., Stump, E. & Rosenberg, G. D. (eds) Dinofest International: Proceedings of a Symposium Sponsored by

Royo-Torres, R., Cobos, A. & Alcalá, L. 2006. A giant European dinosaur and a new sauropod clade. Science 314, 1925-1927.

Taylor, M. P. & Naish, D. 2005. The phylogenetic taxonomy of Diplodocoidea (Dinosauria: Sauropoda). PaleoBios 25, 1-7.

Labels: archosaurs, dinosaurs, Mesozoic, sauropods

FULL POST TO COME LATER TODAY (

After years of suffering all-too-brief mentions, asides and speculative remarks, the oft-alluded-to but long-neglected gigantic diplodocoid sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus has been re-examined. Named by Edward Drinker Cope in 1878, it is known only from scant material (a single partial vertebra and fragment of femur) that – to make a bad situation worse – was somehow lost prior to the 1920s. But scant and lost or not, this material shows that A. fragillimus was immense, and in fact the most immense of all mega-sauropods. Full post to follow soon…

And for the latest news on Tetrapod Zoology do go here.

Labels: archosaurs, dinosaurs, Mesozoic, sauropods

In the previous post we looked anew at the controversial Kayan Mentarang animal: that reddish long-tailed Bornean mammal, photographed in 2003 by a World Wildlife Fund team, and announced to the world in December 2005. Widely hailed by many as a probable civet, it was argued by Chapron et al. (2006) to most likely represent Hose’s civet Diplogale hosei, a poorly known, apparently rare civet named in 1892. But despite the apparent strengths of this identification (and the fact that it came from an authoritative source: one of the authors in particular [Géraldine Veron] is a noted expert on viverrids), it was really a non-starter for several obvious reasons.

In the previous post we looked anew at the controversial Kayan Mentarang animal: that reddish long-tailed Bornean mammal, photographed in 2003 by a World Wildlife Fund team, and announced to the world in December 2005. Widely hailed by many as a probable civet, it was argued by Chapron et al. (2006) to most likely represent Hose’s civet Diplogale hosei, a poorly known, apparently rare civet named in 1892. But despite the apparent strengths of this identification (and the fact that it came from an authoritative source: one of the authors in particular [Géraldine Veron] is a noted expert on viverrids), it was really a non-starter for several obvious reasons.

The Kayan Mentarang animal is reddish-brown while Hose’s civet is dark brown or blackish. Chapron et al. (2006) got round this by arguing either that the animal’s colour had been ‘affected by the flash of the camera’, or that the individual was an unusual colour variant. Both suggestions fail to explain the absence of the pale facial, neck and flank markings present in Hose’s civet. Shuker (2006) noted that – contrary to Chapron et al.’s claims of morphological similarity – the long hindlimbs of the Kayan Mentarang animal made it look more suited for arboreal life than is the predominantly terrestrial Hose’s civet. Furthermore, the Kayan Mentarang animal has really tiny ears while Hose’s civet has far larger ones, and the Kayan Mentarang animal also has (proportionally) a much longer tail than Hose’s civet. So the idea that the Kayan Mentarang animal is actually a specimen of Hose’s civet is poorly founded and not likely.

Hose’s civet not so poorly known

Worth noting here is that – while undeniably rarely recorded and poorly known – Hose’s civet isn’t as rarely recorded and poorly known as some authors have recently been saying. Observations were published in 2002 (Francis 2002) and 2003 (Dinets 2003), and camera-trap photos were taken between December 2003 and March 2004 (Wells et al. 2005): the adjacent image shows one of the latter photos, taken in lowland rainforest in

Worth noting here is that – while undeniably rarely recorded and poorly known – Hose’s civet isn’t as rarely recorded and poorly known as some authors have recently been saying. Observations were published in 2002 (Francis 2002) and 2003 (Dinets 2003), and camera-trap photos were taken between December 2003 and March 2004 (Wells et al. 2005): the adjacent image shows one of the latter photos, taken in lowland rainforest in

The case for the squirrel

Anyway, if the Kayan Mentarang animal isn’t Hose’s civet, what is it? As mentioned above, a new identification has now been published, and hasn’t been as well reported as was the viverrid identification, which is surprising given that it is perhaps the most interesting and surprising idea so far proposed. It would seem that the animal is actually…. a flying squirrel. Despite the fact that it’s only just becoming well known, this theory has been around since March 2006, when Andrew Kitchener published an article on Erik Meijaard’s thoughts about the creature (Kitchener 2006). Both authors are noted mammalogists. Meijaard observed that the creature seems to have ‘the suggestion of a membrane between the front and hind limbs’. I agree, and had always wondered why the animal seemed to have such a deep ‘belly’.

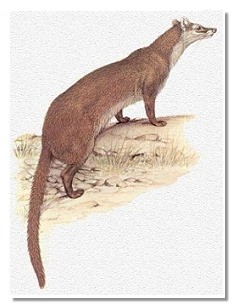

In fact the case for the squirrel identity is strong: by tabulating all the morphological features present in the two photos, and then doing likewise for all 16 similar-sized mammals from Borneo (they included one Sulawesi viverrid too), Meijaard et al. (2006) showed that the Kayan Mentarang animal agrees well in recordable details with two flying squirrels found on Borneo: Thomas’ flying squirrel Aeromys thomasi and the Red giant flying squirrel Petaurista petaurista (taxiderm specimen shown at left, close-up head shot at top of article, and painting shown at bottom of article. Sorry, no picture of A. thomasi to hand). Of the 13 morphological characters available for comparison, A. thomasi matches the Kayan Mentarang animal in 12 of them (the 13th character – orientation of the tail when on the ground – remains uncertain in A. thomasi). In contrast to viverrids, mongooses, linsangs, mustelids, the Bornean bay cat, the Groove-toothed squirrel (aka Tufted ground squirrel) Rheithosciurus macrotis, and various primates, only A. thomasi agrees with the Kayan Mentarang animal in having a short face, small, rounded ears, a reddish non-patterned coat, a tail that exceeds head and body length, and a rounded tail tip. The two also agree in size (the Kayan Mentarang animal is estimated to be 350-450 mm in head and body length) and limb proportions.

In fact the case for the squirrel identity is strong: by tabulating all the morphological features present in the two photos, and then doing likewise for all 16 similar-sized mammals from Borneo (they included one Sulawesi viverrid too), Meijaard et al. (2006) showed that the Kayan Mentarang animal agrees well in recordable details with two flying squirrels found on Borneo: Thomas’ flying squirrel Aeromys thomasi and the Red giant flying squirrel Petaurista petaurista (taxiderm specimen shown at left, close-up head shot at top of article, and painting shown at bottom of article. Sorry, no picture of A. thomasi to hand). Of the 13 morphological characters available for comparison, A. thomasi matches the Kayan Mentarang animal in 12 of them (the 13th character – orientation of the tail when on the ground – remains uncertain in A. thomasi). In contrast to viverrids, mongooses, linsangs, mustelids, the Bornean bay cat, the Groove-toothed squirrel (aka Tufted ground squirrel) Rheithosciurus macrotis, and various primates, only A. thomasi agrees with the Kayan Mentarang animal in having a short face, small, rounded ears, a reddish non-patterned coat, a tail that exceeds head and body length, and a rounded tail tip. The two also agree in size (the Kayan Mentarang animal is estimated to be 350-450 mm in head and body length) and limb proportions.

When the two ‘mystery’ photos are looked at with all of this in mind we see, with hindsight I suppose, hitherto unappreciated squirreley-ness. The way the animal holds its long hindlimbs (referring here to the photo showing the animal from behind) and the suggestion of a patagium now make sense, and the unusual curving shape of the long tail matches the tail posture reported for giant flying squirrels (Meijaard et al. 2006, p. 321) and is unlike that of viverrids and other carnivorans. The white eye-shine present in the Kayan Mentarang animal reportedly matches that of flying squirrels, ‘whereas the civets and cats normally have less bright, yellowish or orange eye-shine’ (Meijaard et al. 2006, p. 321). Look at the image at the top of the article: I’m not too sure about this. To help convince people, Meijaard et al. (2006) have provided two paintings of the Kayan Mentarang animal, this time ‘reconstructed’ using A. thomasi to fill in the gaps.

When the two ‘mystery’ photos are looked at with all of this in mind we see, with hindsight I suppose, hitherto unappreciated squirreley-ness. The way the animal holds its long hindlimbs (referring here to the photo showing the animal from behind) and the suggestion of a patagium now make sense, and the unusual curving shape of the long tail matches the tail posture reported for giant flying squirrels (Meijaard et al. 2006, p. 321) and is unlike that of viverrids and other carnivorans. The white eye-shine present in the Kayan Mentarang animal reportedly matches that of flying squirrels, ‘whereas the civets and cats normally have less bright, yellowish or orange eye-shine’ (Meijaard et al. 2006, p. 321). Look at the image at the top of the article: I’m not too sure about this. To help convince people, Meijaard et al. (2006) have provided two paintings of the Kayan Mentarang animal, this time ‘reconstructed’ using A. thomasi to fill in the gaps.

If Meijaard et al. (2006) are correct, then two factors have helped obscure the animal’s true identity. Firstly, there is the frustrating fact that its face is obscured by some vegetation, or, as WWF’s Head of Borneo programme director Stuart Chapman put it, ‘As with all good yeti shots, there is a leaf that obscures its snout’ (Fair 2006). I don’t quite understand the yeti reference, as there aren’t any photos of purported yetis that have leaves in the way… but, then, there aren’t any good yeti photos at all :) (maybe he was thinking of the Myakka skunk ape photos?). If this really is a squirrel, we would surely all have realised sooner had we been able to see its pointed, distinctively rodent-type snout. Secondly, people just aren’t used to seeing flying squirrels walking around on the ground, which isn’t surprising given that forest-dwelling flying squirrels are arboreal animals of the canopy. It stands to reason that a ground-walking flying squirrel looked unfamiliar, even to Bornean locals with good knowledge of wildlife, and to experienced field biologists.

Of course none of this demonstrates that the Kayan Mentarang animal really is a ground-walking specimen of A. thomasi, and not an unknown species. But I’d say that the case is very good and more likely than the new species hypothesis.

Given that giant flying squirrels are awesome and deeply weird I’m no less impressed by the Kayan Mentarang animal than I was when I thought it likely to be an unusual new viverrid. Some species of Petaurista truly are giants (for squirrels), reaching 2.5 kg and more than 100 cm in total length. Though experts at manoeuvrable gliding, they might undergo periods of occasional flightlessness when, in Spring, they gorge on buds and new leaves.

Given that giant flying squirrels are awesome and deeply weird I’m no less impressed by the Kayan Mentarang animal than I was when I thought it likely to be an unusual new viverrid. Some species of Petaurista truly are giants (for squirrels), reaching 2.5 kg and more than 100 cm in total length. Though experts at manoeuvrable gliding, they might undergo periods of occasional flightlessness when, in Spring, they gorge on buds and new leaves.

As has been noted by both John Lynch and Loren Coleman, of incidental interest in this story is that the squirrel A. thomasi was described by Sir Charles Hose (1863-1929) in 1900*, while the civet D. hosei was described by Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas (1858-1929) in 1892. I also like the fact that Meijaard et al. submitted their paper on April 1st… so far as I can tell this didn’t delay its eventual publication however (woe betide forgetful authors who submit papers announcing bizarre results on April 1st, as Charles Paxton will attest). Note also that I wasn’t planning to blog on the Kayan Mentarang animal so soon, but after John Lynch wrote about it at Stranger Fruit on New Year’s Day (go here) I figured that it was only a matter of time before it become old news. For proof that I’ve been planning to post about the Kayan Mentarang since 2006, look at the last paragraph here.. ha, as if proof were needed.

* Entirely by coincidence, I recently wrote about Hose in the Baikal seal post. I’ve also written about Meijaard’s research before: see The many babirusa species.

And that is that. I just finished writing an article on those green lizards from

Refs - -

Chapron, G., Veron, G. & Jennings, A. 2006. New carnivore species in

Dinets, V. 2003. Records of small carnivores from

Fair, J. 2006. Scientists foxed by new carnivore. BBC Wildlife 24 (1), 30.

Francis, C. M. 2002. An observation of Hose’s civet in

Meijaard, E., Kitchener, A. C. & Smeenk, C. 2006. ‘New Bornean carnivore’ is most likely a little known flying squirrel. Mammal Review 36, 318-324.

Shuker, K. P. N. 2006. Mystery beast in

Wells, K., Biun, A. & Gabin, M. 2005. Viverrid and herpestid observations by camera and small mamal cage trapping in the lowland rainforests on

If I were to produce a list of the 100 most exciting discoveries made in tetrapod zoology within the last few years (which I won’t), then up there in the top 20 - at least - would be the Kayan Mentarang animal. Or, in fact, it would have been up there in the top 20 (at least) for, as we’ll see, a new study has demoted somewhat the potential significance of this creature. You’re doubtless already familiar with it (even if the name Kayan Mentarang doesn’t sound familiar): it’s that unusual reddish long-tailed mammal, photographed by a team from the Swiss World Wildlife Fund at a camera-trap in central Borneo, and widely hailed as a probable new species. If you’re wondering, ‘Kayan Mentarang animal’ is not this creature’s official name: it’s a label that I’ve invented, and one that (in my opinion) is clearly superior to the various other labels that have already been given to the creature. Some writers have referred to it as a cat-fox, while one newspaper article jokingly suggested that it be termed the ‘cat-dog-fox-monkey-lemur’.

If I were to produce a list of the 100 most exciting discoveries made in tetrapod zoology within the last few years (which I won’t), then up there in the top 20 - at least - would be the Kayan Mentarang animal. Or, in fact, it would have been up there in the top 20 (at least) for, as we’ll see, a new study has demoted somewhat the potential significance of this creature. You’re doubtless already familiar with it (even if the name Kayan Mentarang doesn’t sound familiar): it’s that unusual reddish long-tailed mammal, photographed by a team from the Swiss World Wildlife Fund at a camera-trap in central Borneo, and widely hailed as a probable new species. If you’re wondering, ‘Kayan Mentarang animal’ is not this creature’s official name: it’s a label that I’ve invented, and one that (in my opinion) is clearly superior to the various other labels that have already been given to the creature. Some writers have referred to it as a cat-fox, while one newspaper article jokingly suggested that it be termed the ‘cat-dog-fox-monkey-lemur’. Though the two photos that feature the Kayan Mentarang animal were taken in 2003, they were not made public until early December 2005 (the second photo, showing the animal from behind, is featured at left). I don’t know why this postponement occurred, but such delays are fairly ordinary given that scientists are often really, really busy, or hesitant to announce controversial news. Then again, some news is deliberately held back until its release might have the most impact. I don’t want to seem cynical so will stop there, but it’s probably not a coincidence that the discovery was announced at the same time as was news that the Indonesian Government plans to start an oil palm plantation in the vicinity of Kayan Mentarang National Park.

Though the two photos that feature the Kayan Mentarang animal were taken in 2003, they were not made public until early December 2005 (the second photo, showing the animal from behind, is featured at left). I don’t know why this postponement occurred, but such delays are fairly ordinary given that scientists are often really, really busy, or hesitant to announce controversial news. Then again, some news is deliberately held back until its release might have the most impact. I don’t want to seem cynical so will stop there, but it’s probably not a coincidence that the discovery was announced at the same time as was news that the Indonesian Government plans to start an oil palm plantation in the vicinity of Kayan Mentarang National Park.

During December 2005 and January and February 2006 features on the Kayan Mentarang animal appeared in most newspapers, in most science magazines, in Science (Holden 2005), and on TV. Led by Stephen Wulffraat, the WWF team confirmed that local people were unaware of the creature, and they also noted that none of the mammalogists they’d consulted had been able to identify it. While some biologists noted a vague superficial similarity with lemurs, most concluded that it was a viverrid: a member of the same carnivoran family as civets and genets*. Many viverrid species are highly enigmatic and several have only recently been discovered, have only occasionally been photographed alive, or have even not been photographed alive at all (for a nice review see Schreiber 1989).

* Though note that recent phylogenetic studies have agreed that the traditional Viverridae is not monophyletic. Nandinia is not close to civets and genets, but is in fact a basal feliformian (Flynn et al. 2005); oriental linsangs (Prionodon) are not viverrids, but in fact the sister-taxon to cats (Gaubert & Cordeiro-Estrela 2006, Gaubert & Veron 2003); and Madagascan carnivorans are also not viverrids, but closer to mongooses (Gaubert et al. 2005).

Thanks to its long tail, gracile proportions, size (comparable to that of a house cat), and general civet-like appearance, the Kayan Mentarang animal soon became widely regarded as a probable new viverrid. The adjacent painting is a widely-reproduced image, produced by Wahyu Gumelar for WWF Indonesia, depicting the animal as a new, hitherto unknown viverrid. The idea that the Kayan Mentarang animal might be a hitherto-undiscovered species is exciting and easy to take seriously, given the size of Borneo (third biggest island) and the continuing discovery there of many new species. However, some authors were prepared to go further and be even more precise in their identification, and by far the most popular and widely reported identification has been that the Kayan Mentarang animal in fact represented a known species of viverrid: namely, Hose’s civet Diplogale hosei (also known as Hose’s palm civet or the Brown musang) [see image below]. Named in 1892 and known from less than 20 specimens, this is a poorly known terrestrial viverrid of montane forests, and good observations and photos of it are few and far between.

Thanks to its long tail, gracile proportions, size (comparable to that of a house cat), and general civet-like appearance, the Kayan Mentarang animal soon became widely regarded as a probable new viverrid. The adjacent painting is a widely-reproduced image, produced by Wahyu Gumelar for WWF Indonesia, depicting the animal as a new, hitherto unknown viverrid. The idea that the Kayan Mentarang animal might be a hitherto-undiscovered species is exciting and easy to take seriously, given the size of Borneo (third biggest island) and the continuing discovery there of many new species. However, some authors were prepared to go further and be even more precise in their identification, and by far the most popular and widely reported identification has been that the Kayan Mentarang animal in fact represented a known species of viverrid: namely, Hose’s civet Diplogale hosei (also known as Hose’s palm civet or the Brown musang) [see image below]. Named in 1892 and known from less than 20 specimens, this is a poorly known terrestrial viverrid of montane forests, and good observations and photos of it are few and far between.

Arguing that the Kayan Mentarang animal and Hose’s civet were anatomically similar, Chapron et al. (2006) proposed that the alleged new carnivore ‘may not be new’. They clearly weren’t entirely convinced by their own explanation however, as they also noted that the

Arguing that the Kayan Mentarang animal and Hose’s civet were anatomically similar, Chapron et al. (2006) proposed that the alleged new carnivore ‘may not be new’. They clearly weren’t entirely convinced by their own explanation however, as they also noted that the

Sorry, have to stop there. Part II to be posted soon… Lots more on Hose’s civet, and also ‘the reveal’. And if you know the answer (i.e., you’ve read Erik Meijaard et al.’s paper, or you’ve been clever enough to do a bit of surfing and have found the answer on other blogs and news sites), then don’t spoil it for everyone else :)

Oh yeah: happy new year!

Refs - -

Chapron, G., Veron, G. & Jennings, A. 2006. New carnivore species in

Flynn, J. J., Finarelli, J. A., Zehr, S., Hsu, J. & Nedbal, M. A. 2005. Molecular phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): assessing the impact of increased sampling on resolving enigmatic relationships. Systematic Biology 54, 317-337.

Gaubert, P. & Cordeiro-Estrela, P. 2006. Phylogenetic systematics and tempo of evolution of the Viverrinae (Mammalia, Carnivora, Viverridae) within feliformians: implications for faunal exchange between

- . & Veron, G. 2003. Exhaustive sample set among Viverridae reveals the sister-group of felids: the linsangs as a case of extreme morphological convergence within Feliformia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of

- ., Wozencraft, W. C., Cordeiro-Estrela, P. & Veron, G. 2005. Mosaics of convergences and noise in morphological phylogenies: what’s in a viverrid-like carnivoran? Systematic Biology 54, 865-894.

Holden, C. 2005. New species in

Schreiber, A. 1989. Mysterious mustelids, very mysterious viverrids. BBC Wildlife 7 (12), 816-823.